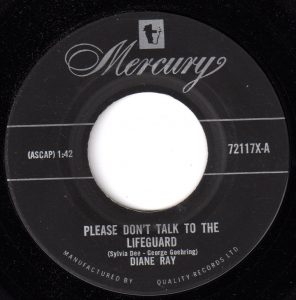

#772: Please Don’t Talk To The Lifeguard by Diane Ray

Peak Month: August 1963

8 weeks on Vancouver’s CFUN chart

Peak Position #4

Peak Position on Billboard Hot 100 ~ #31

YouTube.com: “Please Don’t Talk To The Lifeguard”

Lyrics: “Please Don’t Talk To The Lifeguard”

Carol Diane Ray was born in Gastonia, North Carolina, in 1945. In 1963 Diane Ray graduated from Gastonia High School. Earlier that year she entered a talent contest on a local AM radio station, WAYS, in Charlotte, NC. She had been singing with a band called the Continentals. In the September 7, 1963, Billboard Magazine reported that Mercury Records A & R director (Artists and Repetoire), Shelby Singleton, was on the panel of judges for the WAYS-AM radio contest in Charlotte. Diane Ray won the talent contest and she was signed to Mercury Records. While she went to Nashville to do some more recording, her first single, “Please Don’t Talk to the Lifeguard”, appeared on the Billboard Hot 100.

“Please Don’t Talk To The Lifeguard” featured lyrics by Sylvia Dee. Earlier, Dee wrote “Too Young” for Nat King Cole, a number one hit in 1951. She first gained attention with her novelty song “Chickery-Chick”, a number one hit for Sammy Kaye’s Orchestra in the winter of 1945. In 1963, Sylvia Dee also co-wrote “The End of the World”, a country-pop hit for Skeeter Davis. Sylvia Dee also wrote “Moonlight Swim” for Elvis Presley’s 1961 movie, Blue Hawaii, and for Elvis’ 1968 movie, Speedway, she wrote “Suppose”.

A collaborator on “Please Don’t Talk to the Lifeguard” and a number of other tunes Dee wrote was George Goehring. He wrote songs recorded on albums for Dion, Guy Mitchell and a minor hit for Gene Pitney titled “Half Heaven, Half Heartache”. He also wrote a Top Ten hit in 1959 for Connie Francis named “Lipstick On Your Collar”. That year he also had a #1 hit in Vancouver for Jamie Horton titled “Robot Man”. Goehring was also one of the co-writers for “Hootenanny”, a Top 40 hit in 1963 for the Glencoves.

Wayback Attack writer, Michael Jack Kirby, reveals that “when Diane’s single was released, Gastonia radio station WLTC played the song every ten minutes throughout an entire day, rival station WGAS also put the record in heavy rotation. Diane was offered a chance to do a daily radio show on WLTC. For several months she had a weekday slot from 3:05 to 4PM, a unique distinction considering there were very few female radio hosts to be found anywhere.”

“Please Don’t Talk to the Lifeguard” is a goofy song about a girl who schemes to swim out of bounds into the sea so that a lifeguard will swim out and rescue her. That way she’ll be able to bypass the signage on the beach that instructs “Please Don’t Talk to the Lifeguard”. In the process of being rescued she figures then she’ll be able to get acquainted with the lifeguard. The song was not a minor hit in the USA, only peaking at #31. But in Vancouver, where there are lots of beaches, the song caught on and peaked at #4. The song was originally recorded by Andrea Carroll in 1961 and charted to #1 in Cleveland, Ohio. However, Carroll’s recording didn’t crack the Billboard Hot 100.

In 1963, Diane Ray’s cover of the song did reach the Top Ten in a few other local radio markets besides Vancouver. It actually peaked at #1 in both Miami, Florida, and Calgary, Alberta. And it climbed to#3 in Fort Worth, Texas, #5 in Bakersfield, California, and #8 in Sarasota, Florida. The tune ended up being Diane Ray’s only hit. It was originally a breakout hit in the Houston, Texas, in early July, 1963.

From antiquity, swimming was usually done in the nude or in one’s undergarments. However, by the Middle Ages in Europe swimming was discouraged. By the 18th Century, swimming was viewed as a morally dubious activity. The only reason a person would engage in swimming was if there was a medical recommendation from their physician to do so. In the West, in the 19th century women were required to wear a bathing gown to go swimming. The bathing gown was a loose ankle-length full-sleeve chemise-style made of wool or flannel. In Victorian times it was seen as a way to discourage immodesty. These bathing gowns wouldn’t become transparent when wet. More problematic, these gowns had weights sewn into the hems so that they would not rise up in the water. This resulted in numerous women drowning in their bathing garments.

According to an article in The Philadelphia Inquirer, “Cape May began unofficial rescue operations as early as 1845, with a primitive affair called a “rescue rope.” Ropes hung outside beach bathing houses. If someone summoned help in the roiling surf, whoever heard the call would throw out a line so the victim could grab hold and be pulled to safety.” In 1891, Atlantic City, New Jersey, established the first beach patrol in America with lifeguards.

In the year 1900, in the United States, there were over 9,000 drownings. The California Department of Parks and Recreation reports that one day in the early 1918 thirteen people drowned in San Diego. And eighteen people drowned one week in Newport Beach. During the Great Depression going to the beach to swim was an inexpensive social activity. In response, the state of California began to establish state parks along a strip between Los Angeles and San Diego. By 1937, these included Doheny State Park and San Clemente State Park. A revolution in bathing attire happened in the 1930’s when men, who had previously worn swimsuits (often with stripes) from the knee to the neck, began to go bare chested onto the beach and into the water. By the late 1930’s Orange County began employing lifeguards at their public beaches. Other counties followed suit. After World War II the California Division of Beaches and Parks also began hiring lifeguards at their day beach facilities. When “Please Don’t Talk To The Lifeguard” appeared on the pop charts in the late summer of 1963, the song was referring to a tradition of lifeguards employed on beaches that in most places (Atlantic City, NJ, being among the exceptions) was less than thirty years old.

In Vancouver, our cities first lifeguard was Joe Fortes. He became the cities official lifeguard at English Bay in 1900, making Vancouver one of the first municipalities to have an official lifeguard in North America. Joseph Seraphim Fortes was born in 1863 in the Port of Spain in the British Windward Islands, now known as Trinidad and Tobago. In 1884, Fortes sailed on the Robert Kerr from Liverpool, UK, to Vancouver, BC, via Cape Horn. The Robert Kerr sailed into Vancouver’s Burrard Inlet in September 1885. On the ships log he was listed as Seraphim Fortes, without the “Joe.” Once he arrived in Vancouver Joe Fortes worked shining shoes. During the Great Vancouver Fire of June 13, 1886, Fortes rescued a number of people. The fire destroyed most of the newly incorporated city. Over the following decade Fortes tented on English Bay in the milder months and then took up residence in a cottage on Bidwell Street.

In the 1890’s, Joe Fortes began to patrol English Bay and teach people to swim. Over the years he was credited with rescuing over 100 people from drowning. In 1910, the City of Vancouver gave him a gold watch, a cheque and an illuminated street address. Known as “English Bay Joe” to the locals, Joe Fortes died in 1922. At the time his funeral procession was the largest the city had witnessed, with thousands lining the street. In 1927, a memorial drinking fountain was erected in Alexander Park, across from English Bay. The inscription reads “Little Children Loved Him.” In 1976, the Vancouver Public Library opened the Joe Fortes Library on Denman Street. In 1985, the the Joe Fortes Seafood & Chop House restaurant opened, on the hundredth anniversary of Joe Seraphim Fortes arrival in Vancouver. In 1986, the Vancouver Historical Society named Joe Fortes the “Citizen of the Century.” In 2013, Canada Post issued a commemorative stamp of Joe Fortes.

On September 7, 1963, Billboard ran the following headline: “Diane Ray Collapses at Disk Session.” Due to nervous exhaustion, the singer fainted on the recording studio floor and was rushed to St. Thomas Hospital. The article revealed Diane Ray was to spend a week at the hospital. After that, she would be transferred to a hospital in Gastonia for a further two weeks medical care. Her upcoming tour that included concert dates in Denver, Detroit and Chicago, was called off.

Though she released four more singles with Mercury Records, these were commercial failures. Among these was “Where Is The Boy”. On October 26, 1963, Billboard Magazine listed the tune in their Spotlight Singles of the Week page. The post shouted “Unan-imous! For the gal who made lifeguard famous,” and touted it as a song recommended by music industry magazine Music Vendor as a “sure bet.” However, “Where Is The Boy” made a brief two week appearance on the CFUN-TASTIC FIFTY in Vancouver in November 1963. Elsewhere, the song missed most record surveys across the continent. Of note, “Where Is The Boy” was penned by Mark Barkan and Ben Raleigh. Raleigh had co-written “It’s My Party” for Leslie Gore. And Barkan and Raleigh had co-written “She’s A Fool”, also for Leslie Gore. Mercury Records were hopeful that the song would take off, but no cigar. After 1963, Diane Ray fell off the record charts, off the radar and out of the spotlight. Whatever happened to the “gal who made lifeguard famous” is still to be discovered, as she’s left no online trail behind.

August 29, 2018

Ray McGinnis

References:

Michael Jack Kirby, Diane Ray: Please Don’t Talk to the Lifeguard, Way Back Attack.com

Diane Ray – Credits, Discogs.com

Sylvia Dee bio, Wikipedia.org

George Goehring – Credits, Discogs.com

“Diane Ray Collapses at Disk Session,” Billboard, September 7, 1963

“Spotlight Singles of the Week,” Billboard, October 26, 1963

Jacquline L. Urgo, “On Guard: N.J. Beach Patrols Have Long Been Saving the Day,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, July 11, 2015

History of Lifeguarding in California, California Department of Parks and Recreation

Lisa Anne Smith and Barbara Rogers, Our Friend Joe: The Joe Fortes Story, (Ronsdale Press, Vancouver, 2012).

The History of Metropolitan Vancouver – 1922 Chronology, Vancouver History.ca

Edmunds-Flett, Sherry, Fortes, Joseph Seraphim, Dictionary of Canadian Biography, 2005.

“C-FUNTASTIC FIFTY,” CFUN 1410 AM, Vancouver, BC, August 17, 1963.

For more song reviews visit the Countdown.

what ever happened to Diane Ray

Diane Peoples Waldrop, 74, of Charlotte, North Carolina, passed away March 14, 2020. Born September 1, 1945, in Gastonia, she was the daughter of the late William Arnold and Wilma Irene Lovinggood Ray.

Diane graduated from Ashley High School in 1963. She won the Big Ways Charlotte Talent contest and began her career in music and signed with Mercury Records and went on a short tour before starting her family.

Diane is survived by her loving husband, Samuel McClain Waldrop, Jr.; sons, Robert “Robby” Ray Peoples and Sheldon Lynn Peoples; step-son, Scott Waldrop and his wife, Kimberly; step-daughter, Renay Waldrop; grandsons, Hunter Waldrop and Jordan Peoples; step-grandchildren, Pierson and Presley Bolick; sister, Donna Benfield; niece, Leshea Long; nephew, Jeffrey Long; grand-niece, Kennedy Long and her family; grand-nephew, Kordak Long and his family; and many more loving family and friends.

Due to the current situation with Covid-19 the family will be honoring Diane’s life with a private memorial service.

In lieu of flowers, donations may be made to Levine Children’s Hospital, http://www.atriumhealth.org.

Online condolences may be made at https://hankinsandwhittington.com/tribute/details/179150/Diane-Waldrop/obituary.html#tribute-start

Published in Gaston Gazette on Mar. 22, 2020

I am so sorry to hear this