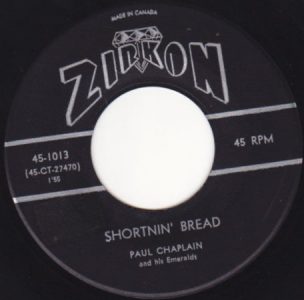

#935: Shortnin’ Bread by Paul Chaplain and his Emeralds

Peak Month: October 1960

7 weeks on Vancouver’s CKWX chart

Peak Position #6

Peak Position on Billboard Hot 100 ~ #82

YouTube.com: “Shortnin’ Bread”

Lyrics: “Shortnin’ Bread”

Paul Chaplain was born in Webster, Massachusetts, in 1934. Not much is written about him on the Internet. By the late 50’s he formed a backing band known as his Emeralds. On Rate Your Music.com, the website states the backing band comprised of these musicians: Tommy Davis (lead guitar), Mike Fiddes (saxophone), Al Marble (piano), Al Weinberg (bass), Eddy Morgan (drums). Whether they were all members at the same time is not clear. Numbers of photos of the band only show four bandmates. In any event, they formed in Webster, Massachusetts. Below a March 23, 2009, YouTube.com posting of “Shortnin’ Bread”, a comment was made by William Gliniecki. He stated: “the original drummer from this band, Eddie Morgan, is still at it, and sits in once a month at an open mic I host in Webster, MA…. I’m going to see Eddie on the 17th again, so I’ll have to pick his brain more about what everyone else is up to now. We host an open mic at the Webster Polish American Citizens Club, and Eddie is a member, so he sets his drums up for general use, and always plays at least 3 or 4 tunes with me & my bass player.”

Another YouTube.com comment from a different post of “Shortnin’ Bread” in 2007 was made by someone who identifies as Rhett Butler. Rhett stated, “I went to Tourtellotte High School in North Grosvenordale Conn. In the late 50’s Paul Chaplain and the Emeralds would play at our high school dances. In fact the drummer Eddie Morgan and I went to basic training in the AF together in 1961. He went to high school with my sister at Bartlett HS in Webster Mass. Thanks for the memory – sadly Paul is gone but the music will never die.”

Chaplains’ first single, released in 1960, was a song from American folklore titled “Shortnin’ Bread”.

Shortnin’ Bread” is often thought of as a traditional plantation song that originated around the year 1800 in the Deep South. In the Folk Song Index website it is stated “the word shortnin’ bread is actually shortbread. It had been popular in England for hundreds of years. The difference with the plantation type and the English type is the brown sugar which gave the South’s short’nin bread a distinctive flavor.” However the first version was written by white poet James Whitcomb Riley in 1900. Riley titled the song “A Short’nin’ Bread Song—Pieced Out” which included this chorus:

Fotch dat dough fum the kitchin-shed—

Rake de coals out hot an’ red—

Putt on de oven an’ putt on de led,—

Mammy’s gwineter cook som short’nin’ bread.

In 1915 E.C. Perrow published the song with the title, “Shortened Bread,” in a collection of songs he’d amassed from his research of folk music in East Tennessee during 1912. Perrow’s folk version of the song didn’t have a coherent theme as some of the verses related to shortnin’ bread while others didn’t. The traditional chorus associated with the folk song had these lyrics:

Mammy’s little baby loves short’nin’, short’nin’,

Mammy’s little baby loves short’nin’ bread

Shortnin’ bread is a fried batter bread, the ingredients of which include corn meal, flour, hot water, eggs, baking powder, milk and shortening. A traditional recipe, adapted for 21st century kitchens, went as follows:

Shortnin’ Bread

2 cups butter

1 cup brown sugar

4 cups flour

1/2 teaspoon salt

Preheat oven to 325 degrees.

Line a 17x 11.5 jellyroll pan with parchment, lightly brush pan with butter. In a large bowl of a mixer, cream the butter, beat in the sugar until very light and fluffy. Turn mixer down to low speed and add the flour and salt., mixing until smooth. (Alternately, the dough may be done by hand). Make sure the butter is very soft and mix it well with the brown sugar. Work the flour and salt in by hand until smooth. This is the way a plantation cook would have done it. Press the dough evenly onto the prepared pan.

Using a sharp knife and a ruler, score the dough into squares, eight on the long side of the pan by six on the shorter side.

Bake for 25-30 minutes or until lightly brown.

Immediately use the sharp knife to cut through the score marks into squares.

Cool thoroughly before serving.

While the tune was a part of American folklore, it only made it to #82 in the USA. A “Mammy” was a black nursemaid or nanny in charge of white children, especially in the deep south. So this Mammy has her hands full with two children, one who had died and the other who is very ill. The remedy for the one remaining child in bed who is still alive is to feed the them Mammy’s shortnin’ bread. One can infer that the shortnin’ bread is a recipe that the child’s Mammy makes herself. Even the doctor agrees that the shortnin’ bread is the best remedy to make the one remaining child well again. It also seems that the child sometimes slipped or sneaked into the kitchen to grab some shortnin’ bread out of a porcelain container and stuff some of these fry bread into their pockets on return to the bedroom.

The history of the term, “Mammy” in American is rooted in the history of American slavery. In her book, Black Feminist Thought, Patricia Hill Collins notes that the average life expectancy of a black Mammie (or Mammy) during the time of slavery was 33.6 years. The black slave mammies were often malnourished and anything but the image of a Mammy that developed in the world of American literature. The image of a black Mammy as matronly, overweight, large-breasted, amiable, loyal, maternal, non-threatening, obedient, submissive and jolly, first appeared in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The novel was published in 1852 and became a best seller with Aunt Chloe as the Mammy archetype. Uncle Tom’s Cabin conveyed the notion that slavery was not hard on slaves and of the convivial relationship between white masters and mistresses with, especially, their Mammies.

Over the decades images of a Mammy found their way into American pop culture. In 1893 a pancake company named itself Aunt Jemima, based on a minstrel song from 1875 titled “Old Aunt Jemima.” Some of the lyrics included:

My old missus promise me,

Old Aunt Jemima, oh! oh! oh!

When she died she-d set me free,

Old Aunt Jemima, oh! oh! oh!

She lived so long her head got bald,

Old Aunt Jemima, oh! oh! oh!

She swore she would not die at all,

Old Aunt Jemima, oh! oh! oh!

Al Jolson had a #2 hit with his song, “My Mammy”, in 1928, after it had been a #1 hit for Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra in 1921. Another iconic image of a black Mammy was Mammy, played by Hattie McDaniel, in the 1939 film Gone With The Wind, based on the 1936 novel of the same name by Margaret Mitchell.

In their book, American Ballads and Folk Songs, John Avery Lomax and Alan Lomax provide an earlier version of “Shortnin’ Bread” in the 19th century:

Two little niggers lyin’ in bed,

one of ’em sick an’ de odder mos’ dead.

Call for de doctor an’ de doctor said,

feed dem darkies on short’nin bread

Mammy’s little baby loves short’nin short’nin

Mammy’s little baby loves short’nin bread.

“Shortnin’ Bread” originated among black slaves on plantations owned by their white masters in the Deep South in America. In the reference to “niggers,” it may have been descriptive of a term the slaves applied to themselves. Of course, this was also the word their white masters used to describe them. When slaves first arrived on ships from Africa in 1619 they didn’t call themselves negroes. The word originally was a Spanish word, negro, meaning “black.” In John T. Coleman’s book about the accounts of Hugh Glass concerning life in American society in 1823, the term, nigger, was alternatively used as a term of endearment and self-respect and as a condescending descriptor. In the 1820’s the term, nigger, was used variously in different parts of the USA to refer to a mountain man as a “dude,” a Mexican, an “Indian” as well as a black slave. In 1859, Harriet Wilson published Our Nig: Sketches from the Life of a Free Black, considered the first novel to be published by an African-American woman in the United States. In the novel the term “nig” is neutral and not pejorative. But the pejorative sense of the word, nigger, quickly came into ascendancy with the American Civil War starting in 1861, and the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in 1866. The rise of Coon songs in Tin Pan Alley from the 1880’s to the end of World War I saw the publication of over 1,500 “Coon songs” that, as a whole, lampooned black Americans as variously lazy, stupid, lustful, violent and untrustworthy. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, founded in 1909, chose the word colored as a descriptor, since “nigger” had by then for decades come to be experienced and understood as a racial slur. In the early 21st century some African-Americans refer to themselves the word nigger, often spelled as nigga and niggah, without irony, either to neutralize the word’s impact or as a sign of solidarity.

In light of the changing view of the word nigger in American society, the word nigger in “Shortnin’ Bread” was replaced with children by the end of the 19th century, if not by the end of the Civil War, when the song was taught to children.

“Shortnin’ Bread” was the first #1 song on the Silver Dollar Survey on WLS AM radio in Chicago when that station began posting a weekly singles chart in 1960, and it also went #1 on WLS’s main competition in the Windy City, WJJD. But aside from some chart action in New York, Pennsylvania and California, the song got little attention. However, it peaked at #6 in Vancouver and #3 on CHUM-AM in Toronto. The B-side of “Shortnin’ Bread” was a screeching anti-cigarette rockabilly number titled “Nicotine” and a promising sign of more to come. As with “Shortnin’ Bread,” Paul Chaplain was the lead vocalist on the song. Chaplain’s single sold over 250,000 copies, a strong sales performance given it’s sales were mostly in New York, Pennsylvania, California, and north of the USA-Canada border in Toronto and Vancouver.

“Shortnin’ Bread” was also the inspiration for Dave “Baby” Cortez’s #1 instrumental hit in 1959 titled “The Happy Organ”. Cortez drew extensively on the melody.

Chaplain tried to have a follow up single but “Swingtime In The Rockies” was a commercial failure. He switched from the New York based Harper label to Elgin Records in Connecticut. But a release on that label failed to chart. A subsequent effort with Pat Records with a cover of “Caldonia” also went nowhere. By the end of 1961 Paul Chaplain and his Emeralds disbanded.

Of the Emeralds bandmates, Joel DiGregorio, who was just 15 when he joined Paul Chaplain to record “Shortnin’ Bread”, went on to some fame. He played keyboards on “Shortnin’ Bread”. DiGregorio had been working at a club called the Golden Nugget in Worcester, Massachusetts, where he played backup for touring recording artists in the R&B scene like Faye Adams and The Drifters. At the age of 14 young Joel had gone to see Ray Charles in concert and recalls he was the only white person in an audience of about 5,000. DiGregorio played clubs in Florida in the mid-60’s and later was noticed by Charlie Daniels and became part of Daniels’ band around 1970. The Charlie Daniels Band opened in 1970 for acts like Delaney and Bonnie. When he joined the band he got the nickname, Taz. Over the years the Charlie Daniels Band toured with other Deep South bands including the Allman Brothers Band, The Marshall Tucker Band, Wet Willie, Lynyrd Skynyrd and Black Oak Arkansas. During his years with the Charlie Daniels Band, Joel “Taz” DiGregorio co-wrote their biggest hit, “The Devil Went Down To Georgia”.

January 31, 2018

Ray McGinnis

References:

Paul Chaplain and His Emeralds, Rate Your Music.com

Angele, 5 Children’s Songs With Racist Histories, Baby & Blog.com, April 29, 2014.

Michael Buffalo Smith, Love the Spider: Taz DiGregorio On Thirty-Plus and Counting Years in The Charlie Daniels Band and His New Solo Album, Swampland, December 2001.

Paul Chaplain and his Emeralds, Rate Your Music.com

William Gliniecki comment, “Shortnin’ Bread,” YouTube.com, March 23, 2009.

Rhett Butler comment, “Shortnin’ Bread,”YouTube.com, October 26, 2007.

Plantation Shortnin’ Bread, Civil War Talk.com, October 3, 2012.

Coleman, John T. Here Lies Hugh Glass. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, NY, 2013.

Collins, Patricia Hill. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness and the Politics of Empowerment. Routledge Classics, New York, NY, 2000 (reprint, originally 1990).

Lomax, John Avery and Lomax, Alan. American Ballads and Folk Songs. Dover Books, New York, NY. 1994.

Keith Allan, The Pragmatics of Connotation. Journal of Pragmatics, Volume 39, Issue 6, pp. 1047–57, Queensland, Australia, June 2007.

Manning, M.M. Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima. University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, 1998.

Stowe, Harriet Beecher. Uncle Tom’s Cabin. 1852.

The History of Minstrelsy: From “Jump Jim Crow” to “The Jazz Singer,” Ragtime and the “Coon song.” USF Libraries.

Ku Klux Klan, History.com.

Wilson, Harriet. Our Nig: Sketches From the Life of a Free Black. 1859. (Reprinted in 2009 by Penguin Books in their History Series, the author in the 1859 printing was identified as “Our Nig”).

“Sensational Sixty,” CKWX 1130 AM, Vancouver, BC, October 17, 1960.

For more song reviews visit the Countdown.

I truly appreciate all of the information on this record, those involved with it, and the places where it was popular. In the early 1960s, I often listened to WLS-890, when I was visiting in Brookline, Massachusetts, where it came in, loud-and-clear, most any night, and also in the early morning (until maybe two hours after sunrise, when it would fade gradually away). I also listened to WJJD-1160. But that one signed-off a couple of hours after sunset, to make way for KSL from Salt Lake City. I also spent many fond summer days in Oxford, Massachusetts — south of Worcester and not far from Webster (back in the 1950s, I used to be able to pronounce the name of that lake — but please do not ask me to attempt it now!). Webster had a low power daytime station on 940, about 250 watts — but you listened to 1310-WORC from Worchester (at least, during the day — it could be a little rough at night!). WBZ-1030 dominated at all times, and then there was 1510-WMEX. 1520-WKBW blasted in from Buffalo, as did 1010 WINS from New York, and WMGM-1050. Sorry, WABC — but nobody bothered, because they never played a record until it was up near the top of the charts everywhere else and you already were sick of it; worse, they played the same 25 songs again and again and again! (you talk about “SAFE” programming!).

And of course, being ABC NETWORK, they had quirks about certain songs. The played Dick Flood and not The Browns on “The Three Bells”. And they were about the ONLY station east of the Mississippi which bothered with the Hollywood Argyles’ version of “Alley Oop”: if you were anywhere in the Northest, that hit was by Dante and the Evergreens! (Billboard notwithstanding — check Cashbox!). All I can tell you is, as summer was waning in 1960, and school was set to re-open for a new fall year; when you heard the first opening blast of Paul Chaplain’s “Shortnin’ Bread”, that set the mood! (The Bell Notes had a somewhat similar version out at the same time, but that one didn’t quite pack the same impact…my opinion). Such a short time ago: how did we all get to be around 80-years-old (give-or-take) suddenly? — can someone please tell me that?

I’m a bass player from Mass and used to play with Paul during the 80’s and 90’s off and on. I met all the members of his band at various times. Eddie, the drummer, was a kid when he recorded that tune (16 or 17, forgot his exact age) so he couldn’t go out on the road with the band. I did play with Eddie years later though after Paul had passed away. Paul was a nice guy and easy to play with. My band was a three piece band and we’d feature him and always close with Shortnin’ Bread. Some nights he played the whole gig, other nights no. I was younger than he was but liked the fifties music. We used to play ‘Nicotine’, the B side of the 45 too. He had a lot of funny stories about the road. We had a steady two night gig in a club in Webster and that’s where I met the former members and where I played with Eddie. People still treated him like a star though, we used to play all around the area, also all around Connecticut.

I left a comment here, I used to play with Paul years afterward, if it doesn’t show up please contact me I’ll rewrite it,

Bob

Thanks Bob!