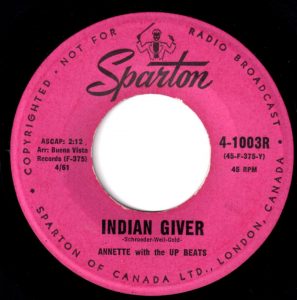

#1044: Indian Giver by Annette with the Up Beats

Peak Month: May 1961

8 weeks on Vancouver’s CKWX chart

Peak Position #8

Peak Position on Billboard Hot 100 ~ did not chart

Peak Position on Music Vendor ~ #107

YouTube.com: “Indian Giver”

Lyrics: “Indian Giver”

Annette Joanne Funicello was born in Utica, New York in 1942. In 1955 she began her professional career as a child performer at the age of twelve when Walt Disney discovered her performing as the Swan Queen in a dance recital of Swan Lake at the Starlight Bowl in Burbank, California. She became one of the most popular Mouseketeers on the original Mickey Mouse Club. As a teenager, she became a pop singer and shortly after an actress in a series of films popularizing the successful Beach Party genre alongside co-star Frankie Avalon during the mid-1960s. On July 17, 1955 Annette Funicello made her television debut during the live broadcast of Disneyland’s opening day ceremonies. She participated in a song and dance routine promoting the upcoming debut of Walt Disney’s new television show, The Mickey Mouse Club. Following the shows premier on Monday, October 3, 1955, The Mickey Mouse Club became an immediate hit. Its army of small, amateur mouse-eared stars took America by storm. It wasn’t long before the young audience of boys and girls developed a particular interest in a little dark haired girl named Annette. Just as she had appealed to Walt Disney himself, when he discovered her at a dance recital, Annette emerged as a favorite among many children across the USA, launching her into television stardom. As a result she appeared on numerous magazine covers and a variety of Disney branded merchandise.

Walt Disney took advantage of Annette’s talents and popularity by featuring her in several Mickey Mouse Club serials, such as The Further Adventures of Spin and Marty and The New Adventures of Spin and Marty. He eventually gave Annette a twenty episode serial of her own, simply titled Annette, during what would be the shows final season. Following the cancellation of The Mickey Mouse Club in 1959, Annette was the only mouseketeer to remain under contract with Disney. The Mickey Mouse Club did, however, appear in re-runs well into the 1960s.

Annette’s solo music career began in 1958 while her serial Annette, was airing on The Mickey Mouse Club. During a hayride scene in one of the episodes, Annette sang what was meant to be a hokey ballad called “How Will I Know My Love,” complete with juice harp and miniature accordion. As a result of Annette’s rendition her friend Laura apologizes for being previously critical of the song.

After the episode aired, thousands of fans called the studio asking where they could buy the record. It was then Walt Disney met with Annette and announced he was signing her to a recording contract. With panic in her voice Annette responded, “But Mr. Disney, I don’t sing. You know I don’t sing”. Disney arranged for Annette to work with Tutti Camarata, a famous musician, arranger, and record producer who had previously worked with other recording artists including Frank Sinatra, Bing Crosby and Ella Fitzgerald. Camarata also brought in The Sherman Brothers as composers, who would come to call Annette “their lucky star” due to the success they found in working with her.

Following the successful release of “How Will I Know My Love”, it was decided that Annette’s next record would be aimed toward the Rock and Roll market, which at the time was practically uncharted territory for a female artist. “Tall Paul,” her second single was recorded and released by March of 1959. It reached number seven on the Billboard chart. With rock and roll instrumentation overpowering her soft voice during the recording sessions, the Shermans and Tutti developed the “Annette Sound.” This was a method of double tracking Annette’s voice and adding echos. In 1959 Annette began what would become a long time professional relationship with Dick Clark when she made her first appearance on American Bandstand singing “Tall Paul”. She also joined Dick Clarks Caravan of Stars that year, a bus concert tour across the country with other teen idols.

Although uncomfortable being thought of as a singer, Funicello had a number of hit records in the late 1950s and early 1960s, mostly written by the Sherman Brothers and including “Tall Paul,” “First Name Initial,” “O Dio Mio” and “Pineapple Princess.” But after “Pineapple Princess,” which peaked at #11 on the Billboard charts and #1 in Vancouver, Annette had trouble getting on the Billboard Hot 100, never mind any more Top 40 hits. “Dream Boy” barely made the Hot 100, stalling at #87, though it made the Top 20 in Vancouver. Her next twenty single releases, beginning with “Indian Giver,” missed the Billboard Hot 100. But in Vancouver, “Indian Giver” caught on and made the Top 10.

“Indian Giver” was co-written by Aaron Schroeder, Cynthia Weil and Wally Gold. Aaron Schroeder had been writing hits for Elvis Presley including “A Big Hunk Of Love”, “It’s Now Or Never”, “Good Luck Charm”, Stuck On You” and others. Schroeder also produced a number of hits for Gene Pitney including “Town Without Pity”, “Only Love Can Break A Heart” and “(The Man Who Shot) Liberty Valance”. Wally Gold was the manager and member of a traditional pop group called The Four Esquires who had some minor hits in the late 1950’s. He co-wrote “It’s Now Or Never” and “Good Luck Charm” with Aaron Schroeder. Gold also co-wrote “It’s My Party”, a hit for Lesley Gore in 1963, and “Because They’re Young”, a hit for Duane Eddy in 1960. Cynthia Weil is known mostly as a successful member of a songwriting team with her husband, Barry Mann. Weil co-wrote many songs with Barry Mann including “Don’t Know Much” for Aaron Neville and Linda Ronstadt, “Hungry” for Paul Revere And The Raiders, “Somewhere Out There” for Linda Ronstadt and James Ingram, “(You’re My) Soul And Inspiration” and “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling” for the Righteous Brothers, “On Broadway” for The Drifters.

It has been said that to err is human. Perhaps it is also true that to stereotype is human. Terms like Indian Giver have been objected to by Native North Americans who find the term derogatory. Many non-Native people now agree. Indian Giver has been an expression used by non-native people to describe a person who gives a gift (literal or figurative) and later wants it back. It is in this connotation that Annette’s “Indian Giver” is meant. She complains in the song that the guy in her life gave her kisses, “then you took your lips away. You’re just an Indian Giver, and you think it’s smart. Hey Mr. Indian Giver, Indian Giver, give me back your heart.”

As observed and documented by Lewis and Clark in their journal, trading with Native Americans had a very unusual aspect, as understood by European settlers. Any trade, once consummated, was considered a fair trade. If on one day beads were traded for a dog from a tribe, days later, the trade could be reversed. Upon surrendering the beads, the tribe expected the dog back. The original idea of “giving” in this fashion connotes trade ~ “I’ll give you this, and you give me that” ~ and not presents or “gifts.” The phrase originated, according to researcher David Wilton, in a cultural misunderstanding that arose when Europeans first encountered the indigenous people on arriving in North America in the 15th century. Europeans thought they were receiving gifts from First Nations peoples like the Algonquian, Huron, Iroquois, Seneca and others. Meanwhile, the First Nations peoples believed they were engaged in bartering. This resulted in the Europeans judging the behavior and customs of the First Nations peoples as ungenerous and insulting. However, the First Nations people intended bartering as a way of establishing relationship and peace between peoples.

In her song, Annette complains, “You said I’d be your pretty little squaw.” The chroniclers of Plymouth colony, William Bradford and Edward Winslow, referred to “the squa sachim, or Massachusets queen” in their entry for September 20, 1621. This reference, published in London in 1622, is the earliest attestation of the word in English. In 1624, Edward Winslow, the governor of Plymouth colony, referred in the 1624 publication, Good Newes from New England to “The squa-sachim, for so they call the sachem’s wife.” Ten years later William Wood of Lynn, Massachusetts, wrote in the 1634 publication, New Englands Prospect: “If her husband come to seeke for his Squaw’.” These published examples show that the English settlers in eastern Massachusetts had learned the word squa(w) as “woman” from their Massachusett-speaking neighbors by 1621 and were using it as an English word by 1634. The expression squa-sachim, literally “woman chief,” is actually in Pidgin Massachusett, the correct Massachusett for “chiefly woman” being sonkusq. The English learned squa(w) and other words via the pidginized form of Massachusett that the local American Indians regularly spoke with them in and around the Boston area. However, the word is not generically applicable across all the First Nations groups in North America. “Squaw” has been used over the centuries by settlers not only as a description of a woman chief in a given tribe, but commonly as a derogatory term connoting a second-class type of person. More controversially, an Algonquin word spelled differently, but sounding the same as squaw, meant vagina. Across indigenous communities in North America, on reserves and in residential schools, the word squaw was used derisively by non-native teachers, principals, police, government officials and neighbors.

Another reference in “Indian Giver” is that Annette sings that she’s going to go “on the warpath.” In popular culture depicted in many Hollywood Western films, American Indians (often white Hollywood actors with make-up dressed up as American Indians) would go on the warpath. But in First Nations culture if there was a decision about going to war against white settlers or another First Nations tribe, a council was held. At the council tribal leaders choose to go on either the warpath or the peace path. Western nations when faced with tensions with other countries often seek a diplomatic solution before resorting to warfare. So it is unfair to label First Nations peoples as particularly warlike. They choose to go on the war path at times and opted for the peace path on other occasions.

In the song, Annette’s backup singers, sing “honest injun.” The spelling, “injun” is a corruption of the word “Indian.” As taught by indigenous Anishinaabe elder and historical interpreter at the Lower Fort Garry National Historic Site (Winnipeg, Manitoba), Allen Sutherland, the word “Indian” itself comes from the Italian “In Dio” which means “in (or of) God,” or “belonging to God.” For European colonizers people who were native to the lands they settled were referred to as “In Dio” or the Spanish “En Dios.” According to the Morris Dictionary of Word and Phrase Origins, by William and Mary Morris, in the 19th Century the phrase “honest injun” appeared in the 1876 novel 1876 by Mark Twain titled The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. The term was used both as a compliment, but also in some news stories sarcastically. Later, it came to mean about the same thing as the American phrase, “scout’s honor,” which was a pledge of truth and honesty.

Finally, in the song, “Indian Giver”, Annette sings “your promise to be faithful, what heap big smoke” and the backup singers echo “heap big.” The word “heap” was a qualifier used to nuance a description of something. In the 1832 Oxford English Dictionary it cites American novelist, Washington Irving, who remarks, “Look at these Delawares,” say the Osages, “dey got short legs–no can run–must stand and fight a great heap.” While Washington Irving is describing one indigenous peoples, the Delaware, being described by another indigenous people, the Osage, as short-legged who fight a great heap, this is the novelists description. Silent screen director, Alf Goulding, had a film made in 1919 titled Heap Big Chief. If the term wasn’t original to the indigenous people’s, it was attributed to them and popularized in the mind of the general public by novelists and film makers. In the Washington Irving example, “heap” was synonymous with “deal” as in “fight a great deal,” while in the 1919 silent screen movie “heap” is synonymous with “very,” as in “Very Big Chief.” In the 20th Century the term became derisive connoting a person who can’t use proper English when speaking a sentence.

In the spring of 1961 sensitivities about terms like Indian Giver, warpath, honest injun and squaw were far from most listeners minds. The tune made it to the top ten in Vancouver, peaking at #8. Interestingly, the only other radio market where “Indian Giver” made the Top 20 across North America was in Boston, Massachusetts, peaking at #12.

In 1963 Annette was loaned out to American International for ten movies. She starred in her first non Disney film, Beach Party with her long time friend Frankie Avalon. This campy comedy put a spin on the traditional musical with dialogue and songs directly inspired by the humor and musical tastes of teens at the time. The movie was a great success and spawned four more beach themed-movies: Muscle Beach Party, Bikini Beach, Beach Blanket Bingo and How to Stuff a Wild Bikini. From 1963 to 1965 Annette Funicello and Frankie Avalon became known as the “King and Queen of the Beach”. While working with American International Pictures Annette also starred in Pajama Party and two racing films: Fireball 500 and Thunder Alley. She made cameo appearances in Ski Party and Dr Goldfoot and the Bikini Machine. In 1968 she played Davy Jones’ girlfriend in the Monkees film HEAD before retiring from the big screen for two decades.

In 1965 Annette was married to Jack Gilardi and gave birth to a daughter (Gina) that same year, and had two more children in the early 70s (Jack Jr. and Jason). By the late 60s she shifted her attention from her career to raising a family. Although she had completely walked away from other aspects of her career, Annette never left television. While staying busy being a mom she would agree to guest star on a large number of popular shows and specials over the next two decades including Fantasy Island, Love American Style and The Love Boat. She was the popular spokeswoman for Skippy Peanutbutter for nine years from the mid 70’s through the early 80’s and she took part in countless television, radio, and magazine interviews. In 1992 Annette founded the Annette Funicello Bear Company which produced collectable designer teddy bears. She died in 2013 after living with multiple sclerosis for twenty-one years.

September 13, 2017

Ray McGinnis

References:

Funicello, Annette, and Romanowski, Patricia. A Dream Is a Wish Your Heart Makes: My Story. Hyperion, New York, NY, 1994.

Eudie Pak, Annette Funicello, Original Mouseketeer, Dies at 70, Biography.com, April 8, 2013.

Bikini Beach, American International Pictures, 1964.

Muscle Beach Party, American International Pictures, 1964.

Fireball 500, American International Pictures, 1966.

Thunder Alley, American International Pictures, 1967.

How to Stuff a Wild Bikini, American International Pictures, 1965.

Beach Blanket Bingo, American International Pictures, 1965.

Mickey Mouse Club, ABC, 1955-1959.

Allen Sutherland, Treaty Relations Commission of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Alf Goulding, Heap Big Chief, 1919.

Morris, William and Mary. Morris Dictionary of Word and Phrase Origins. Collins Reference, New York, NY, 1988.

Twain, Mark. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. American Publishing Company, 1876.

Goddard Ives, The True History of the Word Squaw, News From Indian Country, Madison, WI, April 1997.

“Fabulous Forty,” CKWX 1130 AM, Vancouver, BC, May 27, 1961.

For more song reviews visit the Countdown.

Leave a Reply