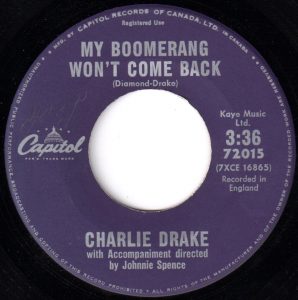

#437: My Boomerang Won’t Come Back by Charlie Drake

Peak Month: January 1962

9 weeks on CFUN’s Vancouver Chart

Peak Position ~ #2

1 week Hit bound

Peak Position on Billboard Hot 100 ~ #21

YouTube: “My Boomerang Won’t Come Back”

Lyrics: “My Boomerang Won’t Come Back”

Charles Edward Springall was born in 1925 in the London neighborhood of Elephant and Castle. In 1933, at the age of eight he began to perform comedy and song at “working men’s clubs,” social clubs for working class men in England. This continued until the start of World War II when Drake served in the Royal Air Force. After the war he eventually pursued a career in entertainment, becoming professional in 1954 with an appearance in a British version of the comedy-crime film Fast and Loose. In 1957 and 1958 he starred in his own BBC comedy show Drake’s Progress. This was followed by Charlie Drake in… which aired from the fall of 1958 to the early spring of 1960. His growing name recognition as a TV star was a catalyst for recording a cover of the Bobby Darin song “Splish Splash”. Drake’s cover climbed to #7 on the UK Singles chart. He followed this with a campy cover of “Volare”, which made the Top 30 in the UK. Drake also covered Frankie Ford’s “Sea Cruise”, with little commercial success. But in February 1960, Drake was back in the Top 20 in the UK with a cover of Larry Verne’s “Mr. Custer”.

In May 1960 the BBC began to air The Charlie Drake Show. In each episode he opened the show with the catchphrase “Hello, my darlings!” The catchphrase came about because he was short, and so his eyes would often be naturally directly level with a lady’s bosom. Because of this and because in his television work he preferred appearing with big-busted women, the catchphrase was born. That year he also appeared in a comedy film Sands of the Desert.

Each episode of The Charlie Drake Show was broadcast live with the slapstick comedy unfolding with the occasional mishap. Only one episode was made for season three as Drake was knocked unconscious during the live transmission of the “Bingo Madness” on October 24, 1961, when a stunt went badly wrong. Drake had arranged for a bookcase to be set up in such a way that it would fall apart when he was pulled through it during a slapstick sketch. But before the broadcast, unbeknownst to the actors, a diligent workman had “mended” the bookcase. The actors working with Charlie Drake, unaware of what had happened, proceeded with the rest of the sketch which required that they pick him up and throw him through an open window. Drake fractured his skull and was unconscious for three days. The rest of the TV series was abandoned.

Prior to the accident Charlie Drake had co-written and recorded a novelty song titled “My Boomerang Won’t Come Back”.

In “My Boomerang Won’t Come Back” we encounter lyrics meant to try anyone in 2020 with political sensitivities. The song is set in the “badlands of Australia” where the aborigines are “having a big pow-wow.” A pow wow is a word that derives from the Algonquian powwaw, meaning “spiritual leader.” In North America most Native American and First Nations (Canadian) peoples held pow wows. These were sacred events with a grand entry, usually a prayer to the Great Spirit, a variety of dances, a drumming song, and singing. But a pow wow is not part of the Australian aborigine tradition.

The central concern of the song is that the son of an aborigine chief named Mack – who sports a Cockney accent – can’t make his boomerang come back. In the chorus Drake sings “I’ve waved the thing all over the place/practised till I was black in the face/I’m a big disgrace to the Aborigine race/My boomerang won’t come back!” One might wonder, before Mack began to wave the boomerang all over the place, what color his skin was? As Australian Aborigines are already dark-skinned, the “back in the face” reference pretended ignorance about this fact. Additionally, there was a long controversial tradition about non-black performers wearing “black face” to represent caricatures of black people – such as “the happy-go-lucky darky” in minstrel shows – in the USA, UK, Canada, continental Europe, South Africa and elsewhere. (In the USA the song had a different version with the words “black face” replaced by “blue face.”)

In the song Mack lists his skills which include being able to ride a kangaroo and cooking kinkajou stew. While the use of the letter “k” works alliteratively for kangaroo and kinkajou, it is highly improbable that an Australian aborigine would make kinkajou stew. This is because the kinkajou is a nocturnal tree-dwelling mammal that is found in Central America and from the Andes in Bolivia to the Atlantic Forest in southeastern Brazil.

However, Mack doesn’t know how to make his boomerang come back, as he runs around and waves it. Presumably, none of his other family members or neighbors thought to point out what he needs to do with his boomerang. Consequently, he is banned from the aborigine community. Once on his own in the middle of the desert, Mack worries that he will be bushwhacked. A bushwhacker is an American English term originating from 1809 from the Dutch bosch-wachter (forest keeper), meaning to make ones way through the bush by beating the bushes (to make a trail). By the American Civil War a bushwhacker referred to Union soldiers who took Confederate soldiers by surprise in guerrilla attacks. And so “My Boomerang Won’t Come Back” continues lyrically to draw across several continents to cobble its story together.

After three or four months of sitting in the desert, a witch doctor called George Alfred Black, tells Mack a secret. If he wants his boomerang to come back, he has to throw it. And so, Mack throws his boomerang and it flies miles up in the sky and hits a small plane with a “flying doctor,” and the plane crashes. While Mack tries to figure out how to get some first aid, the witch doctor tells Mack he owes him 14 chickens. (The Royal Flying Doctor Service of Australia was established in 1912).

A witch doctor is a shaman or medicine man. In either case, this is a tradition rooted in Africa, northern India and Nepal. It is not an Australian aborigine term. (In Australia some aborigines had a tradition of a Kurdaitcha who brought in to punish a guilty party by death. This related to the ritual in which the death is willed by the kurdaitcha, known also as bone-pointing. But this was quite different from what is intended in the song.)

Some may argue that in comedy far-fetched scenarios are fair game, weaving together improbable storylines. But, for many radio listeners in 1961-62 these distinctions may have been lost.

In Australian aboriginal culture a boomerang is a throwing stick, traditionally made of bone or wood. boomerangs were also used to decoy birds of prey, thrown above the long grass to frighten game birds into flight and into waiting nets. They were used as percussive musical instruments, battle clubs and hunting weapons. But over the 20th century the boomerang became associated mostly as a sport.

As a novelty song, “My Boomerang Won’t Come Back” was a regional hit in a variety of radio markets. It peaked at #1 in Toronto and Halifax (NS), #2 in Vancouver (BC), Calgary (AB), Denver (CO), Akron (OH) and Sacramento, #3 in San Diego and Great Falls (MT), #4 in Springfield (MA) and Dallas, #5 in Boston and Birmingham (AL), #6 in Worcester (MA), La Crosse (WI), Davenport (IA) and Columbus (OH), #8 in Cleveland and Phoenix, and #9 in Ottawa (ON) and Seattle. In Australia the song topped the national charts in December 1961 and remained there for six consecutive weeks.

Aboriginal Australians date back to at least 50,000 years ago. There are 250 distinct language groups. British settlers started to colonize Australia in 1788. Over the decades the population of 1.25 million Australian Aboriginals decreased due to massacres, impoverishment and disease. From 1910 to 1970 the Australian government forcibly removed a third of the nations aborigines. They were adopted, prevented from speaking their native language and had their names changed. In 2008 the Australian government apologized to its Aboriginal peoples for the “Stolen Generations” who lost their identity as a consequence of federal policies over sixty years. But in 1961 when “My Boomerang Won’t Come Back” was number-one on the Australian pop chart, the forcible removal of aborigines, and indifference to their cultural heritage was generally accepted.

As Charlie Drake continued to recover from his accident, a film that was completed before October 1961 was released in UK movie theaters before Christmas called Petticoat Pirates. In 1963 Charlie Drake had recovered from his bookcase accident and appeared in the comedy film The Cracksman. Also in 1963, The Charlie Drake Show returned to the BBC with new episodes.

From 1965-70 Drake appeared in the British TV sitcom The Worker. In it he played a perpetually unemployed labourer who, in every episode, was dispatched to a new job by the ever-frustrated clerks – Mr Whittaker in early season episodes and Mr Pugh in latter ones – at the local labour exchange. All the jobs he embarked upon ended in disaster, sometimes with a burst of classic slapstick. Sometimes the scenes featured a bewildered Drake himself at the centre of incomprehensible actions by the people employing him. Bookending these sequences were the encounters between Drake and the labour exchange clerk. Running jokes included Drake’s inability to manage the name of the clerk, with Mr Whittaker rendered as Mr Wicketer, and Mr. Pugh as Mi’er. Poo. In one episode from 1969 titled “Hello, Cobbler”, Charlie’s character is hit on the head by a boomerang and hallucinates a bizarre Australian adventure. In the hallucination, Drake and others play Aborigine characters in blackface makeup. When he wakes up he asks, “What happened?” and is told, “Something you’ve always wanted–your boomerang came back!”

Meanwhile, in 1967 Charlie Drake appeared in the British sitcom Who Is Sylvia? and in the comedy film Mister Ten Per Cent. In 1971 Drake appeared in the sitcom Slapstick and Old Lace. In the 1980s Drake turned to more serious roles, appearing in As You Like It in the Ludlow Festival, and in the 1985 BBC production of Charles Dicken’s Bleak House.

In 2015 the Australian Broadcasting Corporation banned “My Boomerang Won’t Come Back”, after listeners complained it was racist. The radio station in question apologized to its listeners explaining that the DJ wasn’t familiar with the song or its lyrics.

October 2, 2020

Ray McGinnis

References:

“The Charlie Drake Show (BBC 1960-1961),” Memorabletv.com, June 9, 2015.

Erin Blakemore, “Aboriginal Australians,” National Geographic, January 31, 2019.

“Kinkajou,” Wikipedia.org.

“What is a boomerang?,” Boomerang Association of Australia, September 15, 1961.

“Natives Dies After Kurdaitcha Man’s Visit,” The Advertiser, Adelaide, Australia, September 20, 1952.

Stephen Dixon, “Charlie Drake: A Brilliant Physical Comedian, he Revelled in Mayhem with Outraged Innocence,” Guardian, December 28, 2006.

“What Is A Pow Wow?,” Nanticoke Indian Tribe, Delaware.

“Royal Flying Doctor Service of Australia,” Wikipedia.org.

“C-FUNTASTIC FIFTY,” CFUN 1410 AM, Vancouver, BC, January 26, 1962.

For more song reviews visit the Countdown.

i remember this one Ray. I always thought it was a Rolf Harris song.